The new year opened with a devastating 7.1 magnitude (6.8 according to the Chinese Government) earthquake in western Tibet amid the freezing winter. Unlike crisis reporting from around the world, not a single international media outlet has been able to directly report from the earthquake affected area to date. In the absence of independent reporting from the ground, the Chinese government’s international communications have largely shaped the discourse over the Dingri earthquake to project the efficiency of China’s response and effectiveness of its governance through its state media. Notably, these communications consistently refer to Tibet as “Xizang,” reinforcing China’s policy of altering Tibet’s name. This report aims to provide a more nuanced perspective. It sheds light on the unsung heroes, explores critical yet unreported details, and examines potential future risks and the broader implications for Tibet and its people once the public memory starts to fade.

The International Campaign (ICT) for Tibet rejects the Chinese government’s propaganda and projection of Tibet earthquake response to the international community as responsible and efficient. The ICT deplores the government of China for stifling the organic and spontaneous Tibetan grassroots efforts to deliver relief-aid to the earthquake affected area. The Chinese government’s non-transparency on the full extent of destruction and death toll in the Dingri earthquake and censoring Tibetans from speaking is despicable. It is highly reprehensible that not a single international rescue team has been able to arrive at the ground to save lives in the critical first days post-earthquake due to China’s stance.

Diplomatic condolence messages from China’s friendly states extended to Beijing certainly does not heal the Tibetans in the earthquake affected area. International development teams and their expertise are needed on the ground for reconstruction and rebuilding, but Beijing’s positioning of self-sufficiency and blockage of international development assistance makes the rebuilding opaque and an opportunity for further sinification of Tibet.

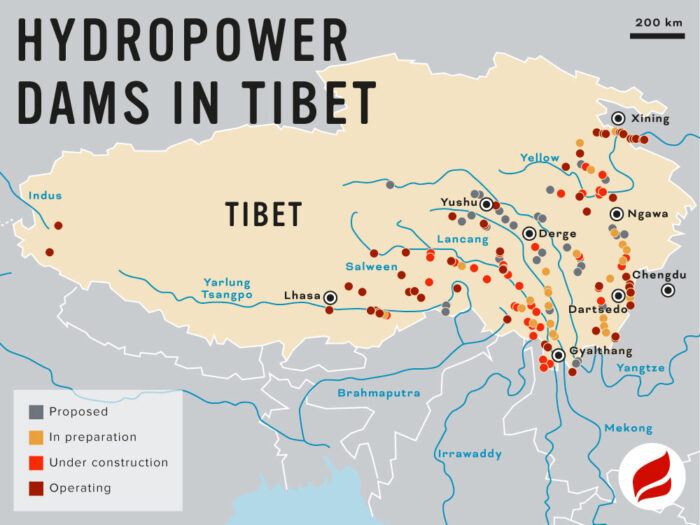

The Dingri earthquake reminds us of the power of nature over the chase for economic growth. China’s rampant dam building spree in Tibet is dangerous to the Tibetans and the downstream countries. China acknowledged that the earthquake has cracked at least five reservoirs in the epicenter zone and at least 1500 people have been evacuated from the course of the river. This reminds the international community on the potential scale of destruction with China’s plan to build the world’s largest dam on Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra) in Tibet. The plan to build the dam, which was approved by the Chinese government last month, must be withdrawn to ensure safety for the Tibetans and the millions living in India and Bangladesh.

Please see here for video clips of Tibetans helping relief efforts.

Tibetan solidarity and unity

Despite the great grief, the Dingri earthquake showed the solidarity and unity of the Tibetan people across the Tibetan plateau. As soon as news of the devastating earthquake spread, Tibetans from all walks of life across the plateau, primarily in and around Lhasa, quickly coordinated relief efforts through Chinese social media, especially video-based apps.

Although news reports, especially the jingoistic Chinese state media outlets, focused on official rescue and relief efforts organized by the Chinese government and military, ordinary Tibetans were the unsung heroes who quickly came together to coordinate relief for the quake-hit areas.

Dispatches of relief and services quickly arrived at ground zero, providing solace, cash, and essential supplies to the grief-stricken Tibetans in the quake zone. As per Tibetan religious custom, groups of monks visited the quake-hit villages to offer prayers and last rites to the dead. In one video clip shared on Chinese social media, a group of monks could be seen visiting villages in the middle of the cold night. Beijing based Tibetan writer and rights activist Woeser in social post wrote that “starting from January 7, 2025, monks from Sakya Monastery quickly rushed to the 15 affected villages in Dingri to hold a memorial service for the victims…The monks traveled to various villages for a day and a night. Wherever they went, they chanted sutras and prayed for blessings, comforting the families of the victims and the villagers. In some villages, the local people embraced the monks and wept when they saw them.”

Clips of truckloads of wood for funeral pyres heading towards the quake zone were shared on social media. In times of great calamities where the number of dead is too large for birds to consume, traditional Tibetan sky burial practices are forgone for cremation. In one video clip, at least seven burning funeral pyres could be seen at an elevated location.

Monasteries across Tibet also coordinated fundraising efforts. Multiple video clips shared on social media showed monks donating their personal savings for the grief-stricken Tibetans in the quake zone.

Ordinary Tibetans across society also mobilized quickly to coordinate aid to the quake-affected area. Tibetan entrepreneurs and artists were prominent on Chinese social media, donating monetary and essential supplies. Video clips of Tibetans helping relief efforts and providing monetary assistance also circulated widely on social media. Tibetan influencers on Chinese social media played a major role in coordinating monetary assistance to the quake-affected families. As proof of accountability to their audience and donors, the influencers shared video clips of themselves handing cash directly to the quake-affected Tibetans and often sharing the stories of the recipient families’ losses in the earthquake.

Grassroots relief efforts stalled

With the immense and quick outpouring of relief and support from the ordinary Tibetans to the quake hit Dingri Tibetans as soon as the news of the devastating earthquake spread, the Chinese authorities stalled the grassroots mobilization of relief presumably on fears of the preferred official narrative on the earthquake from being derailed. The next day after the earthquake, Dingri County in a notice officially suspended relief from the Tibetans and required vehicle permits and built new checkpoints to limit access to the disaster zone for Tibetans willing to help. With no access, the Tibetan donors piled up essential supplies including perishables in front of the government’s local disaster relief management center in the hopes of delivery to the affected people.

Since China already has stringent controls over international aid and international non-profits, international relief efforts to the quake affected Tibetans were minimal. A statement made by the elected leader of the exile Tibetan community on January 12 called for “granting unrestricted and immediate access to international aid organizations and media delegations” and rebuilding efforts taking into account the traditional Tibetan needs and fundamental rights was also quickly dismissed by the Foreign Ministry of the People’s Republic of China.

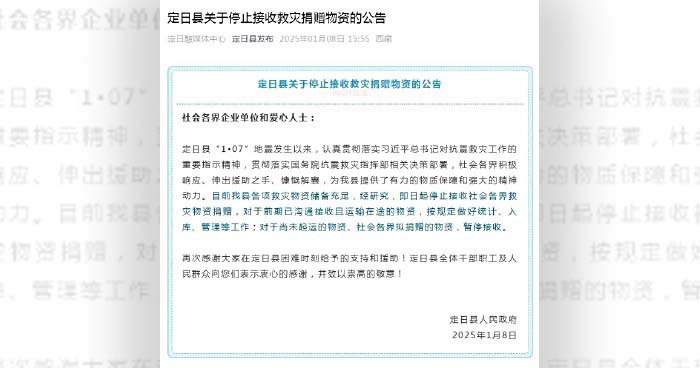

Translation

Since the “1·07” earthquake in Dingri (Tingri)County, all sectors of society have responded positively, extended a helping hand and donated generously, providing Dingri County with strong material support and powerful spiritual motivation.At present, Dingri County has sufficient reserves of various disaster relief supplies. After having discussions, it has been decided to stop accepting donations of disaster relief supplies from all walks of life from now on.

For the materials that have been communicated and accepted in the early stage and are in transit, the statistics, warehousing, and management work should be carried out in accordance with the regulations.

For the materials that have not yet been shipped and the materials that are intended to be donated by all walks of life, the acceptance will be suspended.

The People’s Government of Dingri County

January 8, 2025

Censorship

In order to mold the narrative surrounding the earthquake and its relief efforts to align with their political agenda, both domestically and on the global stage, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Chinese government took measures to control the flow of information. Tibetan influencers, who provided a unique perspective on the plight of the quake affected people, were explicitly cautioned against sharing their views or the stories of those impacted by the disaster.

This pressure from the authorities led to significant self-censorship among these influencers. Instead of sharing firsthand accounts or critical commentary, they began to post messages to their followers, often couched in requests for understanding and patience. This self-censorship was driven by a palpable fear of retribution, reflecting the tight control the government exerts over information dissemination.

One such influencer encapsulated this stifling atmosphere with a poignant reference to a well-known Tibetan proverb: “If one does not control the long tongue, one’s round head will be in trouble.” This saying underscores the perceived danger of speaking out or sharing unapproved information, highlighting the personal risks involved. By invoking this proverb, the influencer not only conveyed the necessity of silence but also subtly critiqued the oppressive environment where free speech is curtailed and where the act of speaking out can lead to severe consequences.

In another video clip, a female influencer shared in her post from the ground that the police ordered her to cease live broadcasting and warned her that her Douyin account (the Chinese version of TikTok) would be suspended. Expressing helplessness, she cautiously displays the relief supplies laid out on the ground and 10,000-yuan cash in her hand, which are to be distributed to the people waiting in line in the background. https://www.youtube.com/embed/CxmaxDLlzhQ?wmode=transparent&autoplay=0

The young man expresses helplessness and states that he won’t talk about Dingri earthquake anymore. Expressing a well-known Tibetan proverb: “If one does not control the long tongue, one’s round head will be in trouble”, the man asks for understanding for his self-censorship. https://www.youtube.com/embed/w1iUmP5Wo6M?wmode=transparent&autoplay=0

The woman says the police ordered her to stop live broadcasting and warned her that her Douyin account would be suspended. https://www.youtube.com/embed/sZ0OfNU6hqk?wmode=transparent&autoplay=0

In a cryptic message facing censorship, the person says that he wants to talk but his ears are being pulled. He says that if he doesn’t take caution, his neck might be cut.

Dingri Earthquake

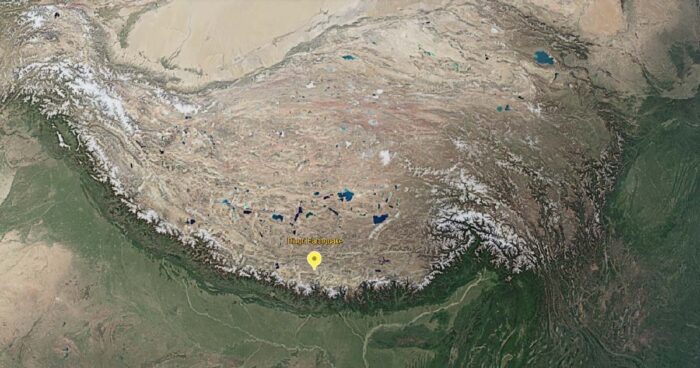

The devastating 7.1 magnitude earthquake that rocked Dingri and beyond occurred at 9:05 am local time on 7 January 2025. What had gone unnoticed and unreported in the news media was a smaller-scale quake that preceded it by almost an hour at the same location at 8:11 am, measuring 3.6 magnitude according to the China Earthquake Administration (CEA). Lives could have been saved if only early warning systems existed for an earthquake-prone region.

Tibet is seismically active as it sits on a major geological fault line where the Indian tectonic plate collides with the Eurasian plate. Twenty-nine earthquakes measuring at least 3 magnitude had occurred in the past five years within 200 km (124 miles) of the 7 January quake epicenter, and 3,614 aftershocks have been recorded by 14 January since then, according to Chinese data.

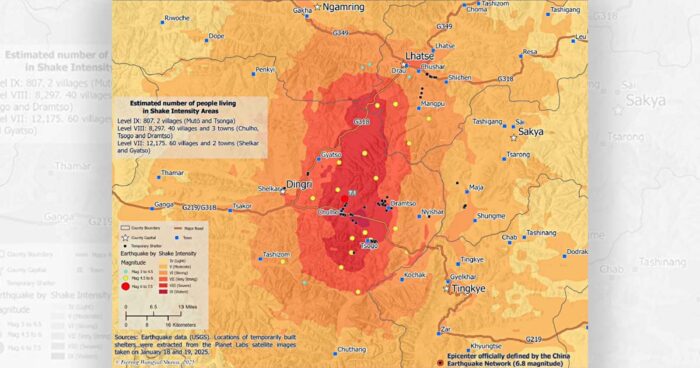

While both the USGS and CEA data were in agreement about the worst affected zone of the earthquake, there were divergences in terms of magnitude and epicenter of the quake. The USGS measured the quake as 7.1 magnitude (Moment magnitude), whereas the CEA measured it as 6.8 (Surface wave magnitude). For the epicenter, the USGS pinpointed it at 28.639°N 87.361°E, whereas the CEA differed, placing it at 28.50°N 87.45°E.

The quake affected zone

A total of one city, six counties and 45 townships in the Tibet Autonomous Region were affected by the earthquake, according to Chinese state media China Central Television on January 10 citing the Ministry of Emergency Management and China Earthquake Administration. The highest intensity zone covered an area of about 411 sq kms affected 5 townships in Dingri county. The 5 townships were named as:

| Tibetan Name of the Township | Township Name in Pinyin | Median Elevation | Population (6th census, 2010) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dramtso | Changsuo | 5,548 meters | 3,601 |

| Chulho | Quluo | 4,618 meters | 3,033 |

| Tsogo | Cuogo | 4,180 meters | 3,556 |

| Nyishar | Nixia | 5,300 meters | 1,827 |

| Gyatso | Jiacuo | 4,744 meters | 1,319 |

Dingri Earthquake

The epicenter and shake intensity map (© Tsering Wangyal Shawa, Princeton University)

A large fault north of Tingmo Lake, Dramtso Township, Dingri County. The upper and lower surfaces on both sides of the largest fault are displaced by about 3 meters. CCTV news, 13 January 2025.

See here for video clips of the quake affected zone.

Death Toll

The earthquake’s death toll has been controversial due to lack of meaningful transparency and censorship by the Chinese government. The determination of the actual death toll is almost impossible just as the number of deaths when COVID hit Tibet.

By 19:00 on 7 January, the official death toll was determined to be 126, after raising it throughout the day. The death toll has been static since then. The official death toll appears to be based on the search operations in 27 villages comprising 6,900 people within the 20 km (12 miles) radius of the earthquake epicenter as the Chinese state controlled media focused on those villages early on. Unofficial death toll through independent research ranged between 134 – 400.

The Voice of America Tibetan Service estimated the death toll to be at least 134 as of 13 January 2025, citing data received from Tibet and confirmed by reliable sources. Unlike China’s official earthquake death toll, VOA disaggregated the death toll as:

| Chulho Township | Tsonga | 3 |

| Tsowar | 3 | |

| Tsotso | 2 | |

| Kyibuk | 3 | |

| Chulho | 2 | |

| Bagha | 5 | |

| Tsogo | Tsogo | 30 |

| Lhatse County | Lhatse | 3 |

| Sakya County | Sakya | 2 |

| Dramtso Township | Serkhar | 17 |

| Gurum | 30 | |

| Nechung | 17 | |

| Karpo | 8 | |

| Gutso | 1 | |

| Jangkar | 3 | |

| Sharlung | 2 | |

| Nesar | 3 |

Citing an interview with a medical staff in a hospital in Dingri county on 11 January, Radio Free Asia Tibetan Service reported, based on the estimate of morgue staff, as stating more than 400 dead in Dingri and Lhatse due to the earthquake.

Inside Tibet, some Tibetans estimate the death toll to be around 265, a figure that has been circulating on the internet within the Chinese firewall. The authorities have refuted this death toll as a rumor and imposed administrative punishment on some Tibetans for spreading “rumors” online. The Chinese government insisted that the official death toll is 126, presenting it as the “truth.” However, the Chinese government has not provided a disaggregated death toll to date.

In the five worst-affected townships, there are 13,336 people, according to the most recent township-level data from the 6th census conducted in 2010. In one video clip shared on Chinese social media, a Tibetan man states that around 100 people are dead in his native Dramtso. The man, who appears to be resting at a tea shop, also answered to the videographer that he had come back from the funeral site, where 13-14 bodies were cremated in the morning.

Potential future risks

China does not waste crises, and this recent earthquake is unlikely to be a wasted opportunity. As China takes full control of the post-earthquake reconstruction, it gives the Chinese government an opportunity to justify further sinification of Tibet and the Tibetan people, and infrastructure development with potential dangers to regional stability, yet highly likely to be presented to the international community as post-quake reconstruction and modernization.

In a highly state-centric development approach, the quake-hit Tibetans are unlikely to have any meaningful participation in the reconstruction just as the Tibetans in Kyegudo (Yushu) experienced after the devastating earthquake in April 2010 that killed around 3000. Reconstruction then was unsatisfactory as Tibetans were disappointed with their town rebuilt in Beijing’s image. 14 years after the Kyegudo earthquake, a retired Tibetan government official and a member of the CCP in December 2024 alleged misappropriation of earthquake relief funds and causing environmental damage in a video statement.

China has been displacing Tibetans from their native hometowns over the years under the policy labels of “poverty alleviation” and “environment protection”. Multiple villages above the 4000 meters sea level have been relocated from their ancestral homes. Since the worst quake affected villages have a median elevation above 4000 meters, the villages under Dramtso, Chulho and Tsogo may face displacement further south towards the border in new Xiaokang border villages.

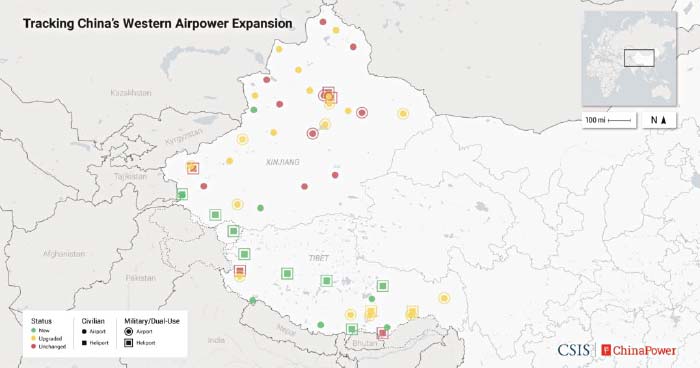

In December 2022, the Development and Reform Commission of the Tibet Autonomous Region announced the “General Aviation Development Plan of the Tibet Autonomous Region (2021-2035).” 14 new airports will be built by 2025 and 58 new airports altogether will be built by 2035, declared the plan. Dingri earthquake provides an opportunity for the Chinese government to justify and accelerate its aerial infrastructure plan in the controversial border areas. Accelerating China’s current action constructing and upgrading dozens of military and dual-use airports and heliports in western Tibet, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies in early 2022.

The largest rivers in Asia begin in Tibet, and China’s rapid development of hydropower dams on these rivers leads to the displacement of Tibetans from their homes and land as reported in ICT’s report Chinese Hydropower: Damning Tibet’s Culture, Community and Environment. This construction also endangers the well-being and health of as many as 1.8 billion individuals throughout China, South Asia, and Southeast Asia.

China Central Television on 15 January reported that five dams in the epicenter zone showed “cracks and other issues” with reporter Liu Jing showing one 560 meters long with 50 cm wide crack at Tsogo reservoir. Describing the risk in the event of a dam collapse, the reporter says, “What’s the real danger of this situation? Let’s look at its surroundings. Our cameraman, following my finger, can see Tsogo Lake in front of me. Tsogo Lake forms a large water surface against the mountains. Below Tsogo Lake is this dam. What’s beyond the dam? Below the dam is a very important road connecting to Dingri. During this emergency rescue operation, it serves as a crucial main artery for transporting rescue personnel and supplies. Looking further down, below this road are some villages. If a major incident were to occur here, with water entering these cracks and threatening the dam structure, and if the dam collapses, the water would rush down, first flooding the road and then the villages.” State media Xinhua a day after stated that monitors have been installed on the Tsogo dam. The report also stated that Laang reservoir in Dramtso Township, Dingri County, “experienced dangers such as tilting of the right side retaining wall of the spillway and water seepage on both sides of the discharge tunnel”. The Tsogo and Laang reservoirs have a storage capacity of 580,000 and 450,000 cubic meters respectively according to Chinese diaspora media.

In response to these findings, Chinese authorities emptied three of the affected reservoirs and relocated at least 1,500 people from villages downstream of the river to mitigate potential risks. This earthquake highlights the vulnerability of large-scale infrastructure projects to natural disasters. The risks of China’s plan to build the world’s largest dam in Tibet is manifold to this despite China portraying this new world’s largest dam as able to withstand earthquakes.