Diplomatic relations between the European Union (EU) and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) were first established in 1975 when Christopher Soames, then European Commissioner for External Relations, became the first EU official to visit the country. Forty year later, China has become the EU’s largest source of imports and the EU is China’s biggest trading partner, and the relationship has grown to include foreign affairs, security matters and international challenges such as climate change and global economic governance. At present, the EU and China hold almost 60 sectorial dialogues and a high-level Summit each year.

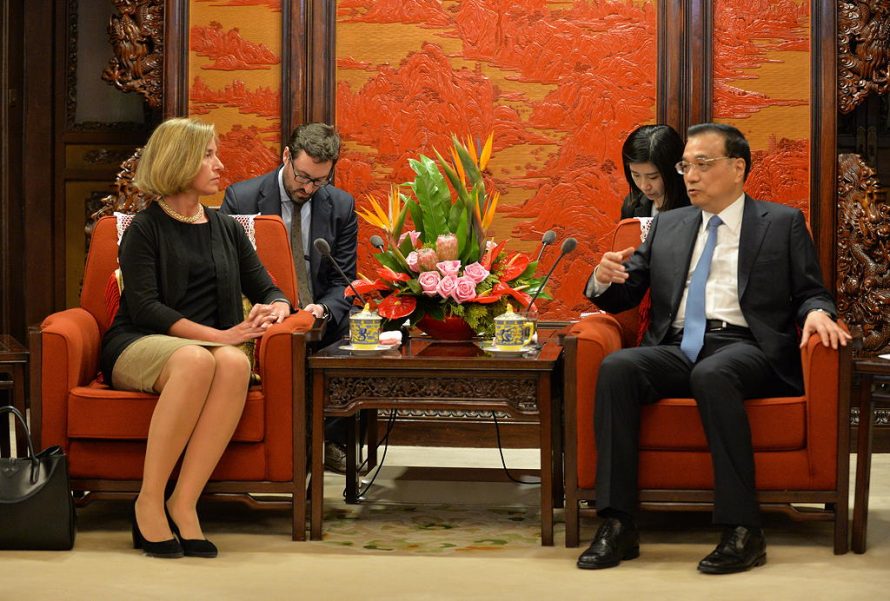

(© European Union)

Today the EU regularly expresses its concerns about the human rights situation in Tibet, including in international forums such as the UN Human Rights Council and statements by its delegation in Beijing. Concerns have also been raised publicly by EU leaders: European Council President Donald Tusk, for example, called for dialogue with the Dalai Lama’s representatives to be resumed after the 17th EU-China Summit in 2015; and following the adoption by the European Parliament of a resolution on human rights in China, High Representative Federica Mogherini stated that the EU “called on the Chinese authorities to allow reciprocal access to Tibet for European journalists, diplomats, and families.” The EU-China Human Rights Dialogue – despite the fact that it lacks clear benchmarks and has so far failed to achieve concrete improvement on the ground – also remains a channel for the EU to raise its concerns directly with the Chinese government.

However, in recent years, the EU has faced increasing difficulties in using combined leverage and speaking with one voice to address China’s human rights record, especially in the case of Tibet, which Beijing considers a strategic and therefore ‘sensitive’ issue. Too often the EU treats human rights as an optional extra in its relationship with China and unified EU positions are becoming increasingly difficult to obtain. This can partly be explained by the increasing confidence of China on the international stage and its growing influence in Europe, but is also a worrying consequence of the lack of unity of European Member States regarding Tibet and human rights in China more generally.

For instance, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, has been used by China as a tool to “divide and rule” Europeans, including on some human rights issues, as some EU Member States have indeed become much more reluctant to criticize Beijing’s egregious record in this field in light of promised Chinese investments. More than half of the EU’s 28 member states have now signed bilateral endorsements of the BRI. The platform of cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries (known as the 16+1 platform, now 17+1 since Greece joined in April 2019), linked to the BRI, is also to a certain extent used by the Chinese government as a tool to do business without having to consider human rights.

Combined with increasing Chinese political influence in Europe – gained through a number of efforts mainly targeting the political and economic elites, media and public opinion and civil society and academia – this lack of unity has led, in recent years, to some EU Member states to embrace Chinese interests, even when they run counter to European interests and the values on which it is based such as the promotion of fundamental rights. This is for example the case of Hungary, which prevented the EU from adding its name to a joint letter denouncing the torture of detained lawyers in China in March 2017, and Greece, which three months later blocked an EU joint statement criticizing China’s human rights record at the UN Human Rights Council.

On Tibet more specifically, China has also adopted a more aggressive diplomatic position on meetings in Europe with the Dalai Lama, stepping up pressure on the EU and its Member States to stop heads of government, ministers and members of Parliament meeting with the Tibetan spiritual leader. In some cases it has even cancell official visits and delegations as retaliation against countries that refused to give into this pressure. In 2008, China for example cancelled the EU-China Summit after Nicolas Sarkozy, then the President of France, who held the EU Presidency, met with the Dalai Lama. China’s 2018 policy paper on the EU specifically tells that “it (the EU) should not allow leaders of the Dalai group to visit the EU or its member states in any capacity or under any name to carry out separatist activities, not arrange any form of contact with officials from the EU and its member states, and not support or facilitate any anti-China separatist activities for “Tibet independence”’. Unfortunately, some European leaders have succumbed to this pressure, ultimately weakening the EU’s leverage on this issue.

Lately, the EU seems to have become more aware of the need to remain united in the face of an increasingly assertive China. A European Commission review of EU-China relations published in March 2019 acknowledges that “China is simultaneously a cooperation partner, with whom the EU has closely aligned objectives … and a systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance,” emphasizing the need for a more balanced relationship with its Chinese partner. But in order to fully rebalance this relationship, the EU must also protect its values and interests by ensuring that its engagement with China remains principled, strategic and united. To do so, the EU must turn into action President Tusk’s declaration after the last EU-China Summit that “human rights are as important as economic interests” and put human rights at the centre stage in its discussions with China.