Until the beginning of this year Atsok Monastery, which was founded in 1889 in Dragkar, Tibet, was home to 160 monks. It has now been completely leveled on the orders of the Chinese government.

The Chinese government has demolished the 135-year-old Atsok (Ch: A’cuohu) Monastery in the northern Tibetan region of Amdo to make way for the construction of a hydroelectric dam. The monastery had previously enjoyed protected status as a cultural heritage site, but this status was unilaterally revoked by Chinese authorities in order to push the demolition forward.

Despite opposition by local Tibetans, work crews began to destroy the monastery in April this year and have now finished.

“We are deeply concerned about the destruction of yet another precious Tibetan Buddhist monastery. Atsok’s cultural heritage status reflected the history of the monastery and its importance to Tibetan Buddhists, and revoking that status in order to destroy it underscores what Tibetans have known all along: China’s attitude towards their religion, history, and culture oscillates from indifference to hostility,” said the International Campaign for Tibet.

From a protected site to a pile of rubble

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) of China, which officially approved the construction of the Yangkhil (Yangqu) dam in 2021, noted in the approval statement that the project had been suspended earlier after learning that it had “started construction without approval.” It is being constructed in Dragkar (Xinghai) county in Tsolho (Hainan) prefecture.

The dam is reportedly the largest robot-built 3D-printed project of its kind. Upon completion, the 1200 megawatt Yangkhyil Hydropower Plant will reach 150 meters in height. It will provide the distant Chinese province of Henan with about 5 billion kWh of electricity every year, with China’s energy needs thus being fueled by the destruction of Tibet’s religious heritage and the displacement of Tibetan communities.

Efforts by the monks of Atsok Monastery and local Tibetans to resist the dam construction have been dismissed by the authorities. RFA reported that the monastic community there “have petitioned authorities to rescind relocation orders” for the past two years. Similarly, Tibet Watch reported that a Tibetan whose identity and whereabouts still remain unknown was taken away by the police following his social media post about the demolition.

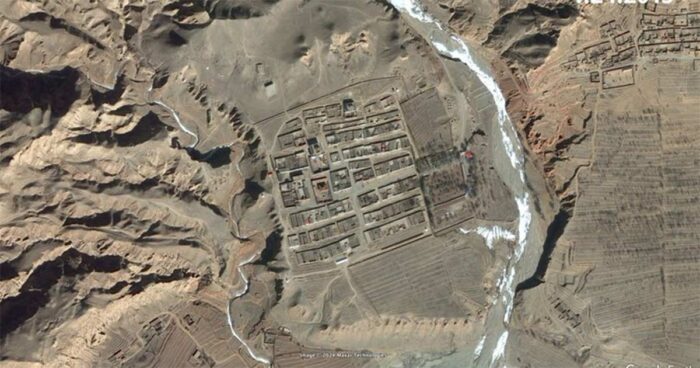

January 2015 satellite image of Atsok Monastery before demolition: Google Earth (35°40’53″N 100°13’11″E)

July 2024 satellite image of the cleared land after the destruction of Atsok Monastery (Image: Radio Free Asia)

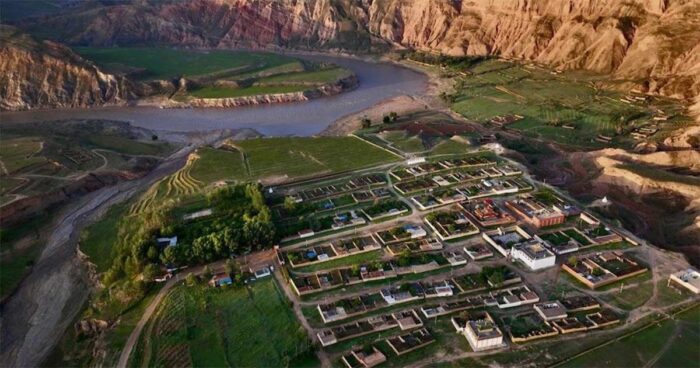

Atsok Monastery at the bend of Machu (Yellow) River. (Image: Tibet Watch sourced from the monastery’s Chinese social media WeChat account)

In April 2023, the Chinese government revoked Atsok Monastery’s status as a county level cultural relic protection site in order to allow the demolition to proceed. In the public notice (see ICT translation below), Dragkar county authorities cited the People’s Republic of China’s Law on Protection of Cultural Relics and related regulations, claiming that the monastery’s main assembly hall and Maitreya Temple were modern imitations and did not qualify as true cultural heritage sites.

ICT could not find any evidence of prior consultations with the monastery before the decision. To the contrary, the Beijing-based Tibetan writer Tsering Woeser, in her social media posts, said the religious community criticized the revocation as a pretextual maneuver to facilitate the demolition of the monastery.

Neither China’s Law on Protection of Cultural Relics nor the Interim Measures for the Management of Cultural Relics Identification have provisions to revoke protected status.

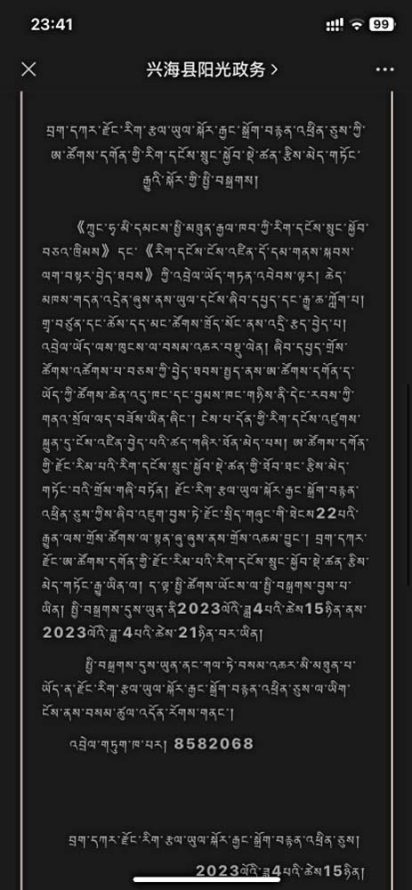

ICT translation from Tibetan of the Dragkar County revocation of Atsok Monastery’s cultural relic protection site status

Public Notice by the Dragkar County Bureau of Culture, Tourism, Radio and TV in invalidating the Relic Protection Division of Atsok Monastery

As prescribed by the “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of Cultural Relics” and “Interim Measures for the Management of Cultural Relics Identification”, through the process of inviting experts to investigate at the actual site, read the documents, to meet and interview monks, nuns, and the religious believing public, to seek views from the relevant offices, to convene investigation meetings, both the existing main Assembly building and the Jampa Temple are modern classic constructions and do not meet the requirements of being recognized as a definitive cultural heritage construction. The proposal has been made to invalidate the status enjoyed by Atsok Monastery as a county level cultural relic protection site.

The County Bureau of Culture, Tourism, Radio and TV investigated and reported to the 22nd standing committee meeting of the county government, and an agreement reached. The county level cultural relic protection site status of Atsok Monastery in Dragkar County is being invalidated. Now it is being publicized to the society at large. The publicization period is from April 15, 2023 to April 21, 2023. During this publicization period, if there are differing opinions, please convey them in writing to the County Bureau of Culture, Tourism, Radio and TV.

Contact Telephone: 8582068

Displaced monks and communities

Starting in December 2021, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and government officials began surveying the site for the “relocation” of the monastery and the displacement of Tibetan villages within the construction zone of the Yangkhil hydropower station. This station is being built at the junction of Dragkar County and Mangra (Guinan) County on the Machu (Yellow) River.

Alongside Atsok Monastery, 22 villages across seven towns in three counties—Dragkar, Beldzong (Tongde), and Mangra—are slated for complete displacement. According to the NDRC’s approval letter, dated November 29, 2021, the project will displace an estimated 7,573 people annually, clearing a total of 13,287 acres (80,691 mu) of land.

The plan dictates that Atsok Monastery will be relocated to a site approximately 3 to 4 kilometers away in the village of Khyokar Naklo. Despite the completion of the demolition, construction at the new site has not yet begun. Local Tibetans report that the monks are living in temporary shelters awaiting the monastery’s reconstruction at the new location, if it happens at all.

Atsok Monastery was by Atsok Choktrul Konchok, and it had previous faced Chinese government interference when the enrollment of minor novice monks was prohibited in 2021.

Following the heritage status revocation the Chinese government held a ceremony for the monastery’s “relocation” and warned local Tibetans against photographing or sharing images of the demolition and hydropower station construction online. Tibet Watch reported the detention of an unidentified Tibetan for sharing such images on WeChat, along with a photo of the Dalai Lama. A foreign tourist, Vera Hue, who visited the site to observe the developments was monitored and expelled by the police.

Official ceremony days before the demolition of Atsok Monastery. The large banner reads “The construction of the relocation of Atsok Monastery in Dragkar county ceremony” (April 2024). CCP and government officials dominate the stage. (Chinese state media photo)

Tibetan faithful prostrating to Atsok monastery on 9 April 2024, in the face of imminent demolition.

(Image: Voice of Tibet)

In a letter to the Tibetan Review, Hue described the experience as “sad and disturbing,” highlighting the ongoing oppression and systematic silencing of Tibetan people under Chinese administration, which discourages foreign witnesses.

Hue’s letter to Tibetan Review based in New Delhi, India, is reproduced in full here.

Witnessing the dismantling of dam-displaced Atsok Monastery in Tibet a sad, disturbing experience

I read your article (TibetanReview.net, Apr 13, 2024) about the relocation of Atsok Monastery in Dragkar Dzong (Ch. Xinhai), Amdo. I happened to be traveling around there in the area and it was easy to go (unlike Wonto monastery in Dege where it is said to be inaccessible and in lockdown) so I went to see for myself what is happening.

I arrived in Atsok monastery without any problems. It is a beautiful, isolated, “antique” as it was described, monastery surrounded by red danxia landforms and snow-capped mountains. But just before getting there, one sees several blue tents (by “civil administration to rescue disaster”) stationed alongside the road and there is a lot of litter everywhere. I walked all over Atsok; it is not a big place anyway, and took many pictures to treasure this site that is not going to be here any longer. A small shrine was open; however, the main temple was unfortunately closed. I asked the monks if they could please open the door for me since, given the relocation, revisiting the place would be literally impossible, but I was told that the key-keeper was away. How heartbreaking, really. When I asked the monks if they had pictures on their phones from the temple interiors that they could perhaps show me, their reply was “the temple has regulations”, and that they are not allowed to take pictures from the monastery and share it. Somebody showed me an odd video (bad quality) with aerial views of the area and that was all. Is there any book I can buy to read about the monastery and its history? No. Is there a webpage where I can read more about the monastery? No.

Atsok Monastery’s demolition in progress. (Photo: Vera Hue)

The place looked and felt unkept and abandoned and in a state of mess as people were dismantling houses and temples and loading stuff onto vehicles to be taken away. So where are they relocating to, I asked. To nearby Hainan (Tibetan Tsholo), was the reply.

After I finished my walk and was about to leave, I was suddenly stopped by five policemen who appeared in front of me out of the blue suggesting to follow them to the police station – which I refused to do. A stern-looking lama then came over and asked me in English who told me about Atsok Monastery and why I am there. They took pictures of my passport and me and my driver’s car plates, and then called their leader and, thankfully, she told them to let me go. The police car followed us all the way back to the main road.

Then, upon returning to my hotel in Dragkar Dzong, 2 policemen and 1 policewoman came to my hotel room to interrogate me, as friendly as they could, about my visit to Atsok monastery and why I took pictures, asking not just a few questions to know more details about me, my background, my work and the purpose of my visit to Atsok monastery and how do I even know this monastery – as it is not on the map. And what am I doing in Xinghai? It’s such a small place, how do I know it?

They stayed for over an hour writing a 3-page report while recording the whole discussion with two cameras.

Excuse me, but what is all this questioning about anyway, it is not a restricted area.

“We are relocating”, said a policeman.

“Oh, really? Why?” I asked, but I got no reply.

When they were finally done, they even recommended me to befriend one of them on WeChat in case I needed further help – a common practice nowadays while traveling in Tibetan areas is that police staff may ask foreign visitors to befriend them on WeChat and unless one doesn’t really mind doing so, one needs to find a polite way to decline it.

Partial demolition of a structure of Atsok Monastery in Tibet. (Photo: Vera Hue)

When it was, at last, time for them to leave, they somehow tried to excuse themselves for taking up so much of my time and I smilingly showed them out saying “You are very welcome. See you later”, because you see, foreigners staying in Dragkar Dzong must first register at the police station and afterwards go check in at a hotel, and then, later during the day, have the police staff pay them a visit in their hotel room for more paperwork and work-photos – at least that is my experience from all the times I’ve been to Dragkar Dzong.

Like in other Tibetan places, non-English speaking Tibetan and Chinese staff in police stations and hotels have hard time deciphering the details of my foreign passport and it takes them an awful lot of time to fill in a registration form. And so, here too, I filled in my registration form myself to save time.

My visit to Atsok monastery was a sad and disturbing experience. And yet another sobering and grounding eye-opener about the shocking reality Tibetan people are faced with on a daily basis in their own land under Chinese administration who doesn’t really like foreigners anywhere near to witness it. To witness a normalised abuse, oppression and persecution that is systematically hushed, muted, dismissed out of hand altogether.

— Vera Hue, 2024