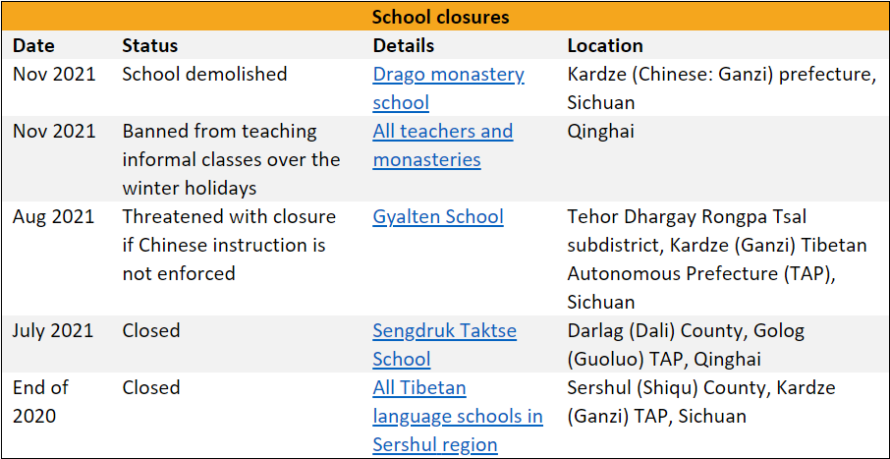

In the eastern Tibetan areas of Amdo and Kham (incorporated into the Chinese provinces of Sichuan, Qinghai and Gansu), where over half the Tibetan population live, numerous reports have emerged of attacks on Tibetan language and Buddhist study.

Last month, Drago Monastery School in Kardze (Chinese: Ganzi) prefecture, Sichuan, was demolished on the grounds of land use violations.[1] The school offered a blend of traditional and modern education, including Tibetan language classes, Mandarin Chinese, English and Buddhist doctrines. The school’s 130 students have since been forced to return home without access to alternative schools with Tibetan language and cultural education. Many more Tibetan instruction schools across Sichuan were closed by the end of 2020, and those remaining have been threatened with closure if they do not switch to Chinese-language instruction.

This same Chinese-language policy is also being pushed across Qinghai. Earlier in July, the Sengdruk Taktse Middle School in Darlag (Dari) County, Golog (Guoluo) Tibetan Autonomous prefecture, Qinghai, was also forcibly closed. Rinchen Kyi, a long-serving teacher, was arrested on Aug. 1 for “inciting separatism” after holding a hunger strike mourning the school’s closure.[2] After the school’s closure, nearby Tibetan-instruction schools were also warned that they may face closure soon.[3]

Similar controls are being imposed on informal language classes. In November, all teachers and monasteries in Qinghai were banned from teaching Tibetan in informal classes over the winter holidays.[4]

End goal to phase out Tibetan language study

A Tibetan scholar of education policy across Tibet (unidentified due to the sensitivity of this topic) argues the recent push to enforce Chinese-language instruction in all schools has roots in the 2008 protests that spread across Tibet. The scholar argues the 2008 protests instigated a more rigorous and accelerated shift in language education policy; one from a model that offered a Tibetan-language education stream (from primary to tertiary education in a few subjects) to a colonial education system that seeks to completely replace Tibetan language and culture altogether.

This also aligned with official national language plans that sought to achieve Chinese-medium instruction in minority areas by the end of 2020; namely the National Long-Term Education Reform and Development Plan (2010-2020) and the Thirteenth Five Year Development Plan for National Language Works (2016-2020). It is notable that when Qinghai province launched its own education reform plan (2010-2020) in 2010, it was heavily resisted and protested by thousands of Tibetan students.[5] The policy was subsequently put on pause in Qinghai, but we may now be seeing the push to complete the planned policy actions.

While some rural areas, as well as small areas of Qinghai, Sichuan and Gansu have been able to resist the shift to Chinese-language instruction with strong and well-organized communities, the independent scholar argues the shift has been broadly achieved across Tibet. They estimate at least 70% of schools across Tibet now use Chinese medium instruction. Sadly, the Tibetan scholar and additional sources suggest that the Tibet Autonomous Region, which spans most of western and central Tibet, has already completed the shift.[6] This may also be the reason why no school closures have been reported from inside the TAR. In the long run, observers believe the goal is to phase out Tibetan language study in five to 10 years.

Targeting pre-school children

Another new policy has been employed in the last few years: Chinese-instruction preschool education. The nationalization of preschool education was launched across China in 2013, and according to the Tibetan scholar, a detailed Tibetan preschool policy was outlined in 2018-2019. The plan for Tibetan preschools sought to teach in the Chinese language only. According to the Tibetan scholar, this policy has a more sinister agenda that aims to replace Tibetan by mandating Chinese language fluency early. Students who do not pass a Chinese language test after preschool are not able to progress into grade one. This means parents who opt-out of Chinese-medium preschools, with an aim to focus on developing a strong Tibetan language foundation, cannot enroll their kids into year 1 if their child fails to pass a Chinese-language test. This hidden agenda is outlined in a 2014 report by the Chinese scholar Yao Jijun, who argued the aim of bilingual preschool education is to “better integrate the Chinese language” into Tibetan children as “a means of eliminating elements of instability in Tibetan regions.”[7]

It is important to note that these recent policies—preschool and Chinese-medium education—are accelerated components of an existing multi-pronged policy to phase out Tibetan language education. For example, Chinese medium-education policies pre-date the 2008 protests, but primarily targeted schools in the TAR. They are now pushing harder in Tibetan regions outside the TAR.

Another preexisting policy is the 2003 school consolidation policy, which replaced village schools with boarding schools in townships. This forced Tibetan children, from the age of 5, to live for at least five days per week away from their families in boarding schools.[8] While kids are allowed to visit home on weekends, it is rare that families can afford the travel costs. As children are taught in the Chinese language, they become disconnected from their families and are less able to understand and navigate Tibetan cultural environments. Tibetan parents and their children are barred from learning and using their language on multiple fronts.

An emboldened “Sinicization” agenda

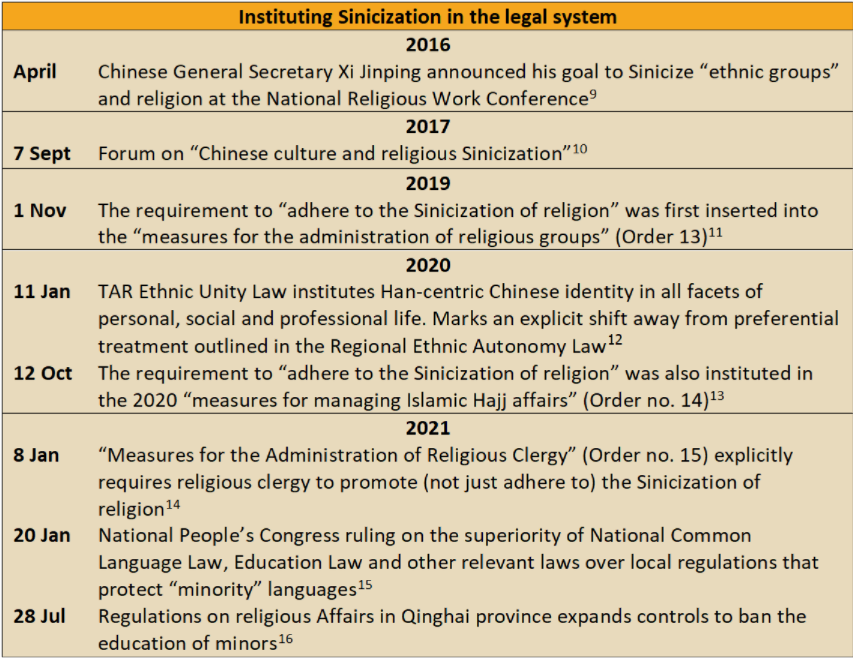

These recent school closures signal the final efforts to eliminate the remaining spaces of living Tibetan culture. They are consistent with China’s “Sinicization” agenda, which seeks to dilute Tibetan identity so that it does not tie Tibetans to each other, their land, history or culture. The end goal is to replace a Tibetan identity with a Han Chinese identity. Numerous policies and laws have been rolled out to this effect (see image 2).

The threat to monasteries

Tibetan Buddhist monasteries will also face renewed attacks on their education and training system. Religious regulations already enforce strict enrollment limits to prevent the spread and preservation of Tibetan Buddhist knowledge, culture, history and identity. However, a recent religious measure passed in Qinghai (Article 49)[17] was used to expel 80 young monks from Jakyung monastery and Ditsa monastery in Bayan County, Qinghai.[18] Authorities indicated minors could not receive a Buddhist education, which aligns with article 49 of the new measure, which specifies: “it is prohibited to hold study tours, summer camps, retreat camps, etc., to spread religion to minors.”[19] A report by Free Tibet notes that the young monks were forcibly returned to their homes and banned from wearing monk robes and attending school. It appears the Qinghai government is taking on a more proactive and assertive position, as the provision on minors is not featured in similar measures released in other provinces.

These more aggressive policies suggest conditions in Tibet will deteriorate even further. A recent conference gathering of over 500 religious figures and students gives an insight into what the future may look like. Government officials at the Buddhist conference at Tso-Ngon Buddhist University in Qinghai recently announced, in the future all Tibetan Buddhist studies must be conducted only in Chinese—not Tibetan—and monks and nuns should only converse in Chinese.[20] Tibetan Buddhism may one day not even use the Tibetan language.

The importance of the Tibetan language

The Tibetan language captures the spirit of a people and their homeland. It carries the values and the collective knowledge of a distinct culture. It is the medium through which Tibet’s 1,300-year history of literature is transmitted and preserved. Tibetan is “one of the oldest and greatest in volume and most original literatures of Asia, along with Sanskrit, Chinese, and Japanese literatures,” according to University of Provence professor Nicolas Tournadre.[21] At a Congressional hearing in 2003 on the Tibetan language and Tibet’s future, David Germano of the University of Virginia forewarned, “by losing the Tibetan language, the specifically Tibetan identity and world, the culture, insights, values and behaviors, is essentially consigned to the past.”[22]

The political climate

The current political climate in China and the COVID-19 pandemic may also help explain why we are seeing these wide-scale controls now. Many China watchers describe a more confident and emboldened Xi Jinping, the president of China, who is undertaking sweeping interventions to address “unresolved” threats to social stability.[23] While Tibet, along with East Turkestan (also known as Xinjiang), Hong Kong and Taiwan are long-standing unresolved issues, Xi Jinping has also been targeting the growth of powerful internet giants, Chinese movie stars and the property market.

Tibetans, and many other rights defenders in China, remain at the mercy of a Communist government that does not represent them, nor even attempt to understand their needs. Despite national Chinese laws that protect Tibetans’ right to learn and use their language, laws in China are only invoked when it expands government powers, but rarely when it protects individual rights.

Bhuchung Tsering, interim president of the International Campaign for Tibet, said:

“We are witnessing an end of an era, where Tibetans, if creative, proactive and careful enough, could find alternative ways to preserve their identity. It is clear now that China has responded to the 2008 protests by accelerating assimilation. They are directly targeting the Tibetan language to sever the ties that bind Tibetans. What we are now seeing in Sichuan and Qinghai are these remaining Tibetan-language schools trying to resist.

“Under China’s Sinicization policy, there is no space for any practice or real preservation of Tibetan identity. Tibetan language can and should only be used for performative purposes; for tourists to consume on signs, on mani stones and in monasteries. It cannot not resemble a real, living and evolving culture.

“Tibetans’ right to learn and use their language, to believe and practice religion are protected in international human rights laws, such as in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and in the Convention on the Rights of the Child, both of which China has ratified, as well as the national ethnic autonomy law. The international community must urgently act before China obliterates a rich cultural world.”

Footnotes:

[1] Free Tibet, 10 November 2021, ‘Tibetan School Forcibly demolished by Chinese State’, https://freetibet.org/news-media/na/tibetan-school-forcibly-demolished-chinese-state.

[2] Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy (TCHRD), 17 September 2021, ‘China enforces compulsory Mandarin Chinese learning for preschool children in Tibet’, https://tchrd.org/china-enforces-compulsory-mandarin-chinese-learning-for-preschool-children-in-tibet/.

[3] Radio Free Asia (RFA), 14 September 2021, ‘China closes Tibetan school in Qinghai, leaving many students adrift’, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/school-09142021135447.html.

[4] A recent regulation banning off-campus training targeting the competitive and unequal tutoring industry across China was passed on July 24, 2021. This regulation titled ‘Opinions on Further Reducing the Burden of Students’ Homework and Off-campus Training in Compulsory Education” may impact extracurricular Tibetan language classes, but these recent bans in Qinghai do not seem to be linked to the broader ban across China.

[5] International Campaign for Tibet, 22 October 2010, ‘protests by students against downgrading of Tibetan language spread to Beijing’, https://savetibet.org/protests-by-students-against-downgrading-of-tibetan-language-spread-to-beijing/.

[6] See Human Rights Watch, 2020, ‘China’s “Bilingual Education” policy in Tibet: Tibet-medium schooling under threat’, https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/tibet0320_web_0.pdf, page 22 and 25.

[7] Human Rights Watch, 2020, page 6.

[8] Yang Bai, 2018, ‘Hybridity and Tibetan language education policies in Sichuan’, Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, Vol. 28. No. 2., page 16.

[9] Xinhua news, 23 April 2016,’习近平:全面提高新形势下宗教工作水平’ (Xi Jinping: Comprehensively improve the level of religious work in the new situation), http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2016-04/23/c_1118716540.htm.

[10] Global Times, 7 September 2017, ‘5 main religions in China agree to sinicize’, globaltimes.cn/content/1065265.shtml.

[11] National Religious Affairs Administration, 30 December 2019,’宗教团体管理办法’ (Measures for the Administration of Religious Groups, Order no.13), http://www.sara.gov.cn/bmgz/322211.jhtml.

[12] 中国西藏新闻网 (China Tibet News), 15 January 2020, ‘西藏自治区民族团结进步模范区创建条例’ (Regulations on the establishment of a model area for ethnic unity and progress in the Tibet Autonomous Region), http://epaper.chinatibetnews.com/xzrb/202001/15/content_10887.html.

[13] National Religious Affairs Administration, 12 October 2020, ‘伊斯兰教朝觐事务管理办法’ (Measures for managing Islamic Hajj Affairs, Order no. 14), http://www.sara.gov.cn/bmgz/344213.jhtml.

[14] National Religious Affairs Administration, 9 February 2021, ‘宗教教职人员管理办法’ (Measures for the Administration of Religious clergy, Order no.15), http://www.sara.gov.cn/bmgz/351322.jhtml.

[15] 澎湃新闻 (The Paper), 20 January 2020, ‘地方立法规定民族学校用民族语言教学,全国人大:不合宪’ (Local legislation requires ethnic schools to teach in ethnic languages, NPC: Unconstitutional), https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_10867982, and TCHRD, 27 January 2021, ‘China’s rubber-stamp parliament declares use of minority languages “unconstitutional”’, https://tchrd.org/chinas-rubber-stamp-parliament-declares-use-of-minority-languages-unconstitutional/.

[16] National Religious Affairs Administration, 9 August 2021,’ 青海省宗教事务条例’ (Regulations on Religious Affairs in Qinghai Province), http://www.sara.gov.cn/flfg/358584.jhtml.

[17] Ibid.,’ 青海省宗教事务条例’ (Regulations on Religious Affairs in Qinghai Province), 9 August 2021.

[18] Free Tibet, 9 November 2021, ’80 Tibetan monks forcibly expelled from their monasteries’, https://freetibet.org/news-media/na/80-tibetan-monks-forcibly-expelled-their-monasteries, and RFA, 4 November, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/forces-11042021160742.html.

[19] National Religious Affairs Administration, 9 August 2021,’ 青海省宗教事务条例’ (Regulations on Religious Affairs in Qinghai Province), 9 August 2021.

[20] Radio Free Asia, 5 October, 2021, ‘China pushes new plan for Tibetan Buddhist study in Chinese only’, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/plan-10052021152731.html.

[21] Dr Nicolas Tournadre’s submission to a 2003 Congressional hearing on Tibetan language. See Congressional-Executive Commission on China, 7 April 2003, ‘Teaching and Learning Tibetan: The role of the Tibetan language in Tibet’s future’, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-108hhrg87398/html/CHRG-108hhrg87398.htm.

[22] Dr David Germano’s submission to a 2003 Congressional hearing on Tibetan language, Ibid., 7 April 2003.

[23] Jeremy Page and Chun Han Wong, 29 May 2020, ‘Beyond Hong Kong, an emboldened Xi Jinping pushes the boundaries‘, https://www.wsj.com/articles/beyond-hong-kong-an-emboldened-xi-jinping-pushes-the-boundaries-11590774190, and Kaiser Kuo, 28 October 2021, ‘Understanding China’s historic changes through informed empathy’, SupChina, https://supchina.com/2021/10/28/understanding-chinas-historic-changes-through-informed-empathy/.